Qt Designer Signals And Slots Tutorial

Signals and slots are loosely coupled: A class which emits a signal neither knows nor cares which slots receive the signal. Qt's signals and slots mechanism ensures that if you connect a signal to a slot, the slot will be called with the signal's parameters at the right time. Signals and slots can take any number of arguments of any type.

- Qt Designer Signals And Slots Tutorial Download

- Qt Designer Signals And Slots Tutorial Free

- Qt Creator Signals And Slots Tutorial

Build complex application behaviours using signals and slots, and override widget event handling with custom events.

As already described, every interaction the user has with a Qt application causes an Event. There are multiple types of event, each representing a difference type of interaction — e.g. mouse or keyboard events.

- I read the Qt manual about signals and slots and I understood how this signals and slots system works - in theory. In practice, I still don't know how to actually use that system in code. For instance, I have a QSlider object that, when I drag the slider, I'd like it to notify the new slider value in a qDebug message.

- Contents: Downloading the Qt SDK - Creating a Simple Project - Qt Creator Modes - Understanding a Basic Qt Application - Differences in Operators - Signals and Slots - Spinners and Sliders - Syncing Widgets and Layouts - Creating a Useful Program - Designing the User Interface - Coding the FindCrap Program - Finishing the getTextFile Function - Finishing up All the Code - Running Our.

Events that occur are passed to the event-specific handler on the widget where the interaction occurred. For example, clicking on a widget will cause a QMouseEvent to be sent to the .mousePressEvent event handler on the widget. This handler can interrogate the event to find out information, such as what triggered the event and where specifically it occurred.

You can intercept events by subclassing and overriding the handler function on the class, as you would for any other function. You can choose to filter, modify, or ignore events, passing them through to the normal handler for the event by calling the parent class function with super().

However, imagine you want to catch an event on 20 different buttons. Subclassing like this now becomes an incredibly tedious way of catching, interpreting and handling these events.

Thankfully Qt offers a neater approach to receiving notification of things happening in your application: Signals.

Signals

Instead of intercepting raw events, signals allow you to 'listen' for notifications of specific occurrences within your application. While these can be similar to events — a click on a button — they can also be more nuanced — updated text in a box. Data can also be sent alongside a signal - so as well as being notified of the updated text you can also receive it.

The receivers of signals are called Slots in Qt terminology. A number of standard slots are provided on Qt classes to allow you to wire together different parts of your application. However, you can also use any Python function as a slot, and therefore receive the message yourself.

Load up a fresh copy of `MyApp_window.py` and save it under a new name for this section. The code is copied below if you don't have it yet.

Basic signals

First, let's look at the signals available for our QMainWindow. You can find this information in the Qt documentation. Scroll down to the Signals section to see the signals implemented for this class.

Qt 5 Documentation — QMainWindow Signals

As you can see, alongside the two QMainWindow signals, there are 4 signals inherited from QWidget and 2 signals inherited from Object. If you click through to the QWidget signal documentation you can see a .windowTitleChanged signal implemented here. Next we'll demonstrate that signal within our application.

Qt 5 Documentation — Widget Signals

The code below gives a few examples of using the windowTitleChanged signal.

Try commenting out the different signals and seeing the effect on what the slot prints.

We start by creating a function that will behave as a ‘slot’ for our signals.

Then we use .connect on the .windowTitleChanged signal. We pass the function that we want to be called with the signal data. In this case the signal sends a string, containing the new window title.

If we run that, we see that we receive the notification that the window title has changed.

Events

Next, let’s take a quick look at events. Thanks to signals, for most purposes you can happily avoid using events in Qt, but it’s important to understand how they work for when they are necessary.

As an example, we're going to intercept the .contextMenuEvent on QMainWindow. This event is fired whenever a context menu is about to be shown, and is passed a single value event of type QContextMenuEvent.

To intercept the event, we simply override the object method with our new method of the same name. So in this case we can create a method on our MainWindow subclass with the name contextMenuEvent and it will receive all events of this type.

If you add the above method to your MainWindow class and run your program you will discover that right-clicking in your window now displays the message in the print statement.

Sometimes you may wish to intercept an event, yet still trigger the default (parent) event handler. You can do this by calling the event handler on the parent class using super as normal for Python class methods.

This allows you to propagate events up the object hierarchy, handling only those parts of an event handler that you wish.

However, in Qt there is another type of event hierarchy, constructed around the UI relationships. Widgets that are added to a layout, within another widget, may opt to pass their events to their UI parent. In complex widgets with multiple sub-elements this can allow for delegation of event handling to the containing widget for certain events.

However, if you have dealt with an event and do not want it to propagate in this way you can flag this by calling .accept() on the event.

Alternatively, if you do want it to propagate calling .ignore() will achieve this.

In this section we've covered signals, slots and events. We've demonstratedsome simple signals, including how to pass less and more data using lambdas.We've created custom signals, and shown how to intercept events, pass onevent handling and use .accept() and .ignore() to hide/show eventsto the UI-parent widget. In the next section we will go on to takea look at two common features of the GUI — toolbars and menus.

- Categories: python , tutorials

- #pyqt , #python-3 , #qt , #rad

- 9 minutes read

Confession: I am the opposite of the lazy coder. I like doing things thehard way. Whether it’s developing Java in Vim without code completion,running JUnit tests on the command line (don’t forget to specify all 42dependencies in the colon-separated classpath!), creating a LaTeX graphthat looks “just right”, or writing sqlplus scripts instead of usingSQL Developer (GUIs are for amateurs), I always assumed that doing sowould make me a better programmer.

So when I was just a fledgling programmer, and I had to design andcreate some dialog windows for a side project of mine (an awesomeadd-on toAnkiSRS written in Python and Qt), I didwhat I always do: find a good resource to learnPyQt and then code everything by hand.Now, since Python is a dynamic language and I used to develop thisadd-on in Vim, I had no code completion whatsoever, and only the Qtdocumentation and that tutorial to go by. Making things even moreinteresting, is that the documentation on Qt is in C++, and is full ofstuff like this:

Obviously, I had no idea what all the asterisks and ampersands meant andhad to use good-old trial and error to see what would stick in Python.Now, on the plus side, I experimented quite a lot with the code, but nothaving code completion makes it really hard to learn the API. (And evennow, using PyCharm, code completion will not always work, because ofPython being a dynamically-typed language and all. I am still looking atthe Qt documentation quite a bit.)

One thing I noticed, though, is that the guy who develops Anki, DamienElmes, had all these .ui files lying around,and a bunch more files that read: “WARNING! All changes made to thisfile will be lost!”. Ugh, generated code! None of the dedicated,soul-cleansing and honest hard work that will shape you as a softwaredeveloper. It goes without saying I stayed far away from that kind oflaziness.

It took me some time to come around on this. One day, I actually got ajob as a professional software developer and I had much less time towork on my side-projects. So, when I wanted to implement another featurefor my Anki add-on, I found I had too little time to do it theold-fashioned way, and decided to give Qt Designer a go. Surprisingly, Ifound out it can actually help you tremendously to learn how Qt works(and also save you a bunch of time). Qt Designer allows you to visuallycreate windows using a drag-and-drop interface, then spews out an XMLrepresentation of that GUI, which can be converted to code. Thatgenerated code will show you possibilities that would have taken a longtime and a lot of StackOverflowing to figure out on your own.

So, to help other people discover the wonders of this program, here is alittle tutorial on how to do RAD and how to get a dialog window up andrunning with Qt Designer 4 and Python 3.

Installation

First, we need to install Qt Designer. On Arch Linux, it’s part of theqt4 package and you’ll also need python-pyqt4 for the Pythonbindings. (On Ubuntu, you have to install both qt4-designer and thepython-qt4 packages.)

Our goal

Our goal is to create a simple dialog window that has a text input fieldwhere we can type our name, and have a label that will display “Hellothere, $userName”. Yes, things will be that exciting. Along the way,we will learn how to assign emitted signals to slots and how to handleevents.

Creating a dialog

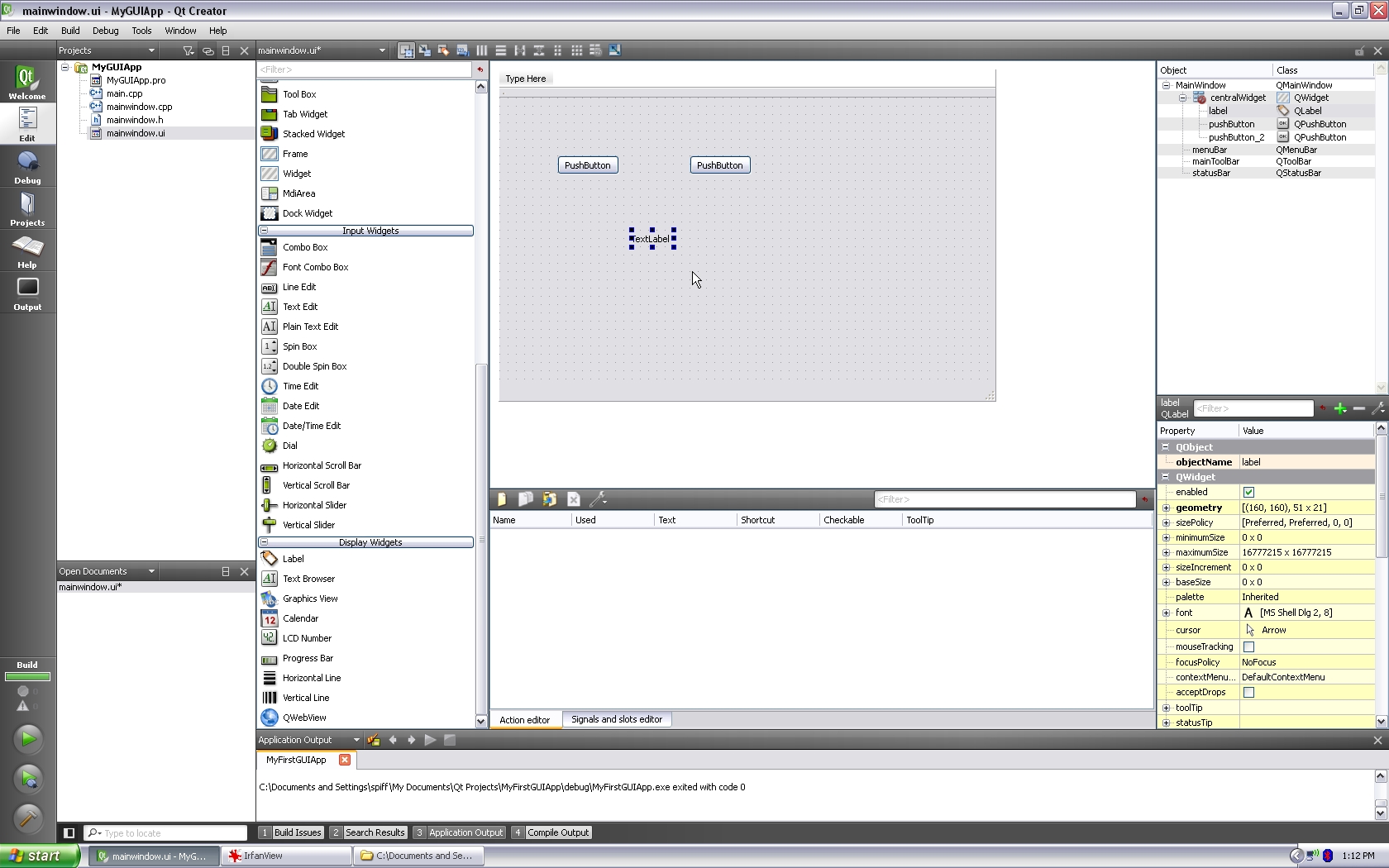

Fire up Qt Designer, and you will be presented with a “New form” dialog(if you do not see it, go to File > New…).

For this tutorial, we are going to choose a fairly small “Dialog withButtons Bottom”:

To the left are the widgets that we can add to our freshly createddialog, to the right, from top to bottom, we see the currently addedwidgets, the properties of those widgets and the signals and slotscurrently assigned to the dialog window.

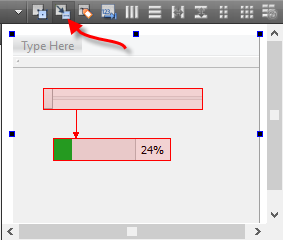

I’m going to add a text label and a so-called line editor to our widget.To make sure they will align nicely, I will put them together in ahorizontal container, a QHBoxLayout:

In the object inspector, we can see the hierarchy of added widgets:

This is all simple drag-and-drop: we select a widget from the left pane,drag it to the desired location in the dialog and release the mouse.

Finally, we add two more label: one at the top, instructing the userwhat to do, and a second one near the bottom, where we soon will displayour message.

Qt Designer provides an easy way to connect signals to slots. If you goto Edit > Edit Signals/Slots (or press F4) you will be presented witha graphical overview of the currently assigned signals and slots. Whenwe start out, the button box at the bottom already emits two signals:rejected and accepted, from the Cancel and Ok button respectively:

The signals rejected() and accepted() are emitted when the canceland OK buttons are clicked respectively, and the ground symbols indicatethe object that is interested in these signals: in this case the dialogwindow itself. Signals are handled by slots, and so the QDialog willneed to have slots for these signals. The slots (or handlers) are namedreject() and accept() in this instance, and since they are defaultslots provided by Qt, they already exist in QDialog, so we won’t haveto do anything (except if we want to override their default behavior).

What we want to do now is “catch” the textEdited signal from the lineeditor widget and create a slot in the dialog window that will handleit. This new slot we’ll call say_hello. So we click the line editorwidget and drag a line to anywhere on the dialog window: a ground symbolshould be visible:

Qt Designer Signals And Slots Tutorial Download

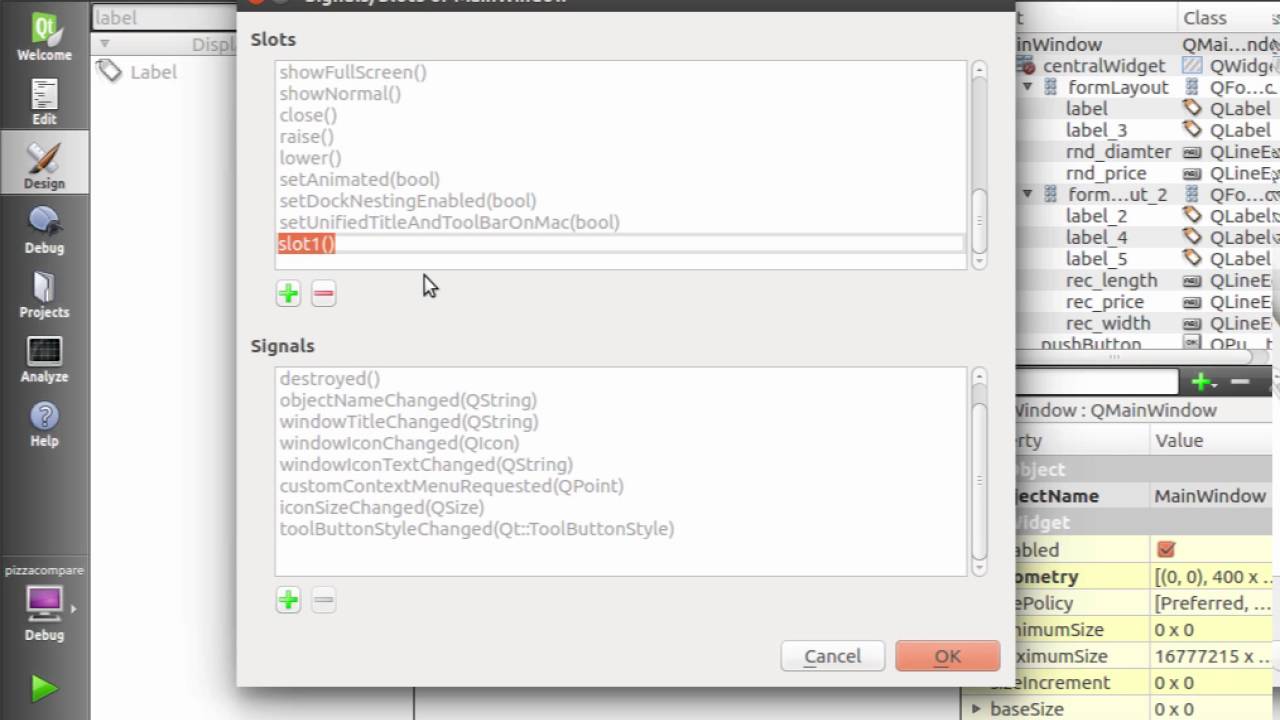

In the window that appears now, we can select the signal that we areinterested in (textEdited) and assign it to a predefined slot, or wecan click on Edit… and create our own slot. Let’s do that:

We click the green plus sign, and type in the name of our new slot(say_hello):

The result will now look like:

In Qt Designer, you can preview your creation by going to Form >Preview… (or pressing Ctrl + R). Notice, however, that typing text inthe line editor won’t do anything yet. This is because we haven’twritten any implementation code for it. In the next section we will seehow to do that.

You can also see the code that will be generated by going to Form >View code…, although this code is going to be in C++.

Okay, enough with designing our dialog window, let’s get to actualPython coding.

Generating code (or not)

When we save our project in Qt Designer, it will create a .ui file,which is just XML containing all the properties (widgets, sizes, signals& slots, etc.) that make up the GUI.

PyQt comes with a program, pyuic4, that can convert these .ui filesto Python code. Two interesting command-line options are --preview (or-p for short), that will allow you to preview the dynamically createdGUI, and --execute (or -x for short), that will generate Python codethat can be executed as a stand-alone. The --output switch (or -o)allows you to specify a filename where the code will be saved.

In our case, creating a stand-alone executable is not going to work,because we have added a custom slot (say_hello) that needs to beimplemented first. So we will use pyuic4 to generate the form class:

This is the result:

It is here that you can learn a lot about how PyQt works, even thoughsome statements seem a bit baroque, like the binding of thetextChanged signal to our custom slot:

If you would write this yourself, you would probably prefer:

(Incidentally, the text between the square brackets intextChanged[str] indicates that a single argument of this type ispassed to the slot.)

Bringing it all together

Having generated our form class, we can now create a base class thatwill use this class:

When we are passing self to self.ui.setupUi, we are passing thewidget (a QDialog) in which the user interface will be created.

We implement our custom slot by defining a method say_hello that takesa single argument (the user-provided text from the line editor). Wecraft a witty sentence with it, and set it as the label text.

As mentioned before, we could also dynamically create the GUI directlyfrom the .ui file:

Running the application

Qt Designer Signals And Slots Tutorial Free

Qt Creator Signals And Slots Tutorial

Running this will show the following (drum roll):